Despite the four-deep horn section, Skunk Hollow Blues has a three-part counterpoint on the head, some solo space with simple riff backgrounds, and one of the gnarliest shout sections of the swing era, all at a tempo perfect for beginner dancers and written with utmost efficiency. Written by Johnny Hodges and arranged by Duke Ellington, Skunk Hollow Blues has a lot to say in under three minutes, so let’s do a deep dive and figure out what makes this unassuming chart so incredible.

The Head

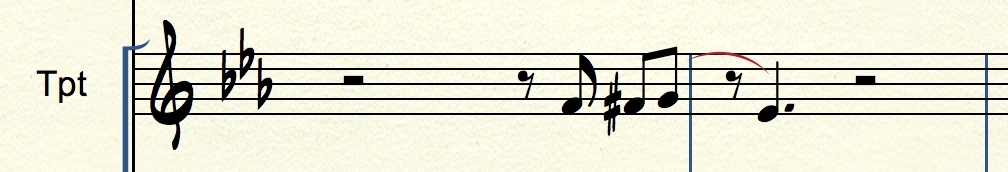

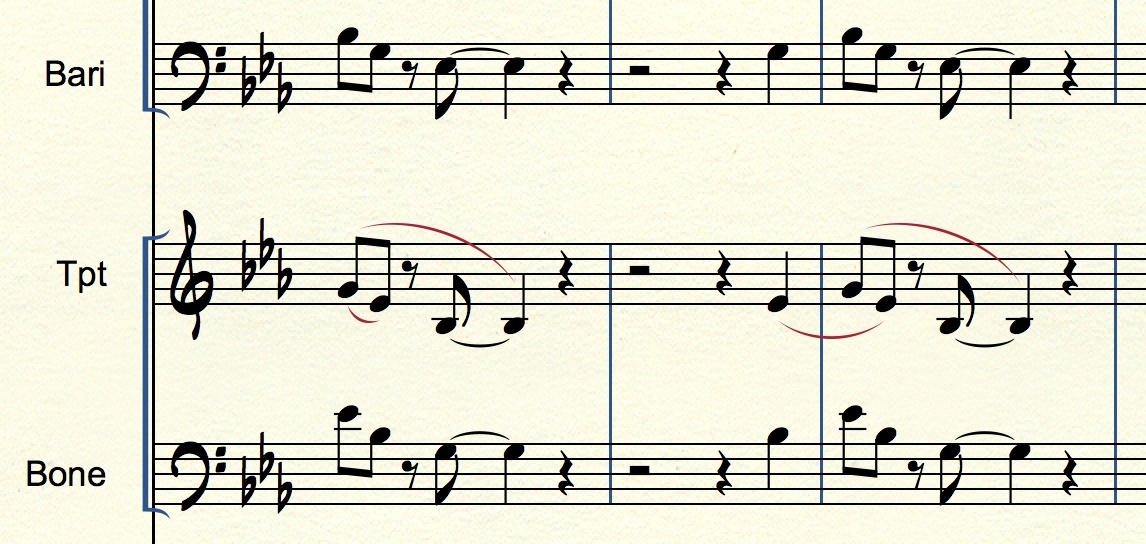

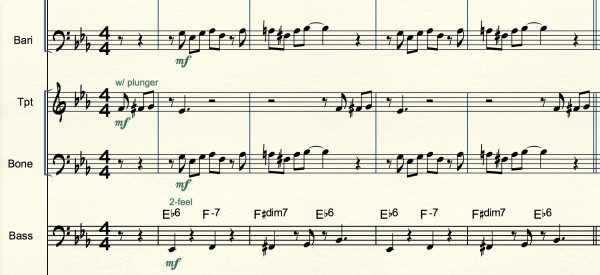

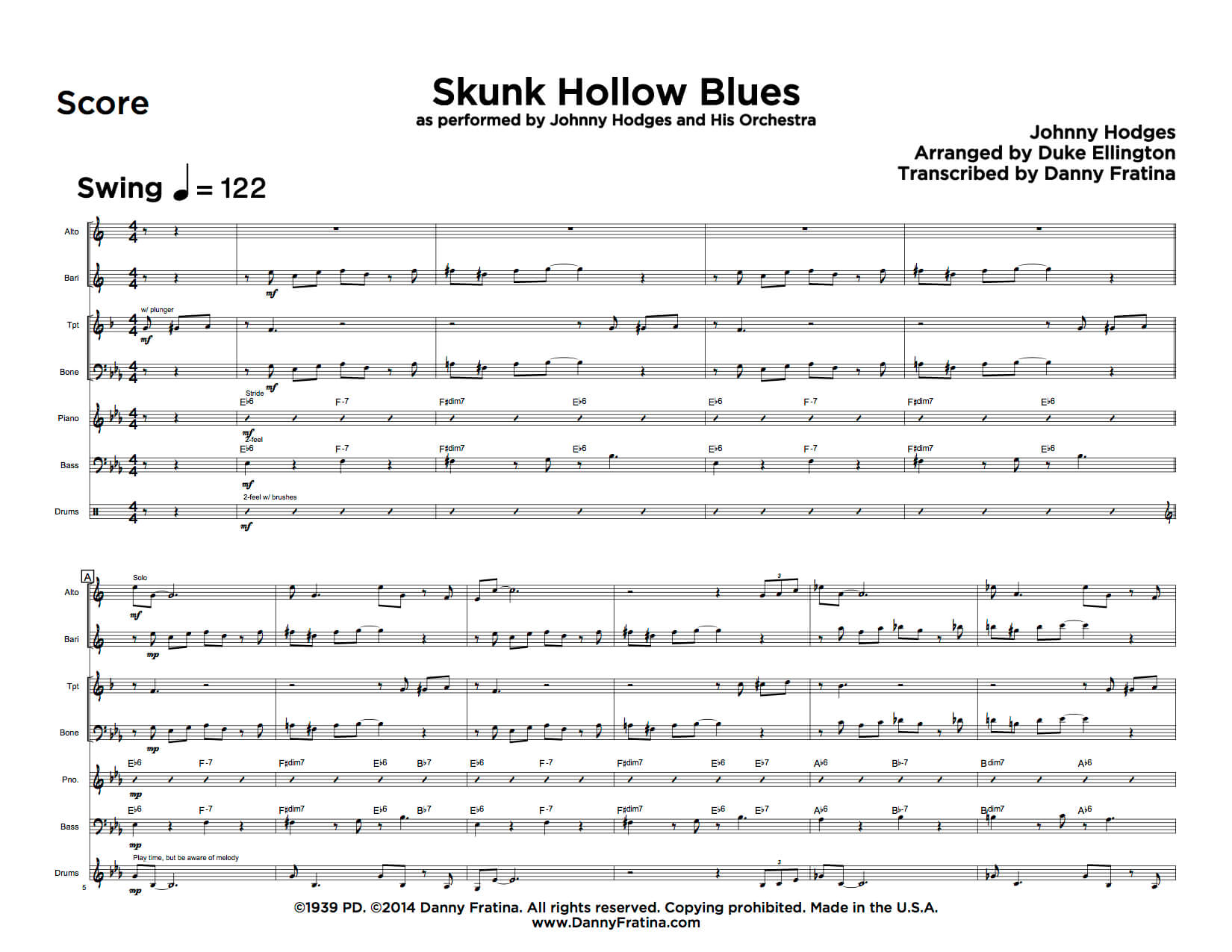

From the first notes by Cootie Williams you can tell something special is coming. The plunger trumpet riff is simple and effective, leaving lots of space as a call for the response from the bari and trombone. That duo works in 3rds with the bass, which arguably might qualify as a 4th piece of counterpoint. The motion of the harmony gives extra color to an otherwise simple blues, and adds small waves of tension and release every two bars.

Note the emphasis on the interval of a third (phrase markings indicate the intervals), which defines both the initial trumpet melody and the horn counter-melody:

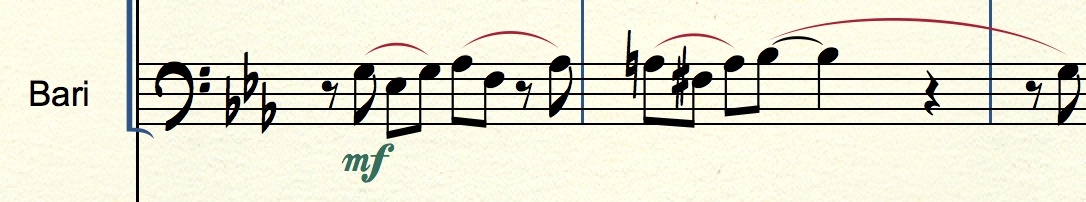

After four bars of this, the alto comes in, contrasting in several ways. An obvious one is that the alto line has longer sustained notes with less motion, compared to the trumpet line which is minimal in melody and length, and the counter line which is note-y and has more room to breathe. A more subtle contrast is that the alto phrase cuts across four bars, while the two background lines only lay over two bars before repeating. The most subtle detail about the alto melody though is that it literally flips the motivic anchor of the two background lines – the interval of a 3rd – and exists based on the inverse of that – the interval of a 6th.

Because this tune was written by Johnny Hodges, it seems safe to assume that, in looking for accompanying material for the arrangement, Ellington took inspiration from the melody first, mining it for material to “recycle.” He saw the 6th in the melody, so he wrote the inversion for the backgrounds — he saw 4-bar phrases in the melody and wrote 2-bar phrases in the backgrounds. The melody informed the background material; it wasn’t written in a vacuum.

Finally, an major component of traditional a blues can be found here involving the statement-statement-resolution formula. An archetypal blues will be 12-bars long, and you can divide that into three 4-bar phrases. Going back to its roots, the first 4-bar phrase will introduce a melodic statement, the second 4-bar phrase repeats that statement, and the final 4-bar phrase resolves or contrasts that statement. If a blues had lyrics, it would tell a story something like this:

It rained all day and night and I couldn’t go outside

It rained all day and night and I couldn’t go outside

I couldn’t see my baby ’cause I couldn’t go outside.

When lyrics aren’t present and you are only working with a melody, you have to contrast that third phrase with rhythm and tones/intervals. Hodges gives you that new third phrase, but Ellington’s arrangement digs in harder for that contrast and drops the 3rds/6ths intervals for stepwise 2nds:

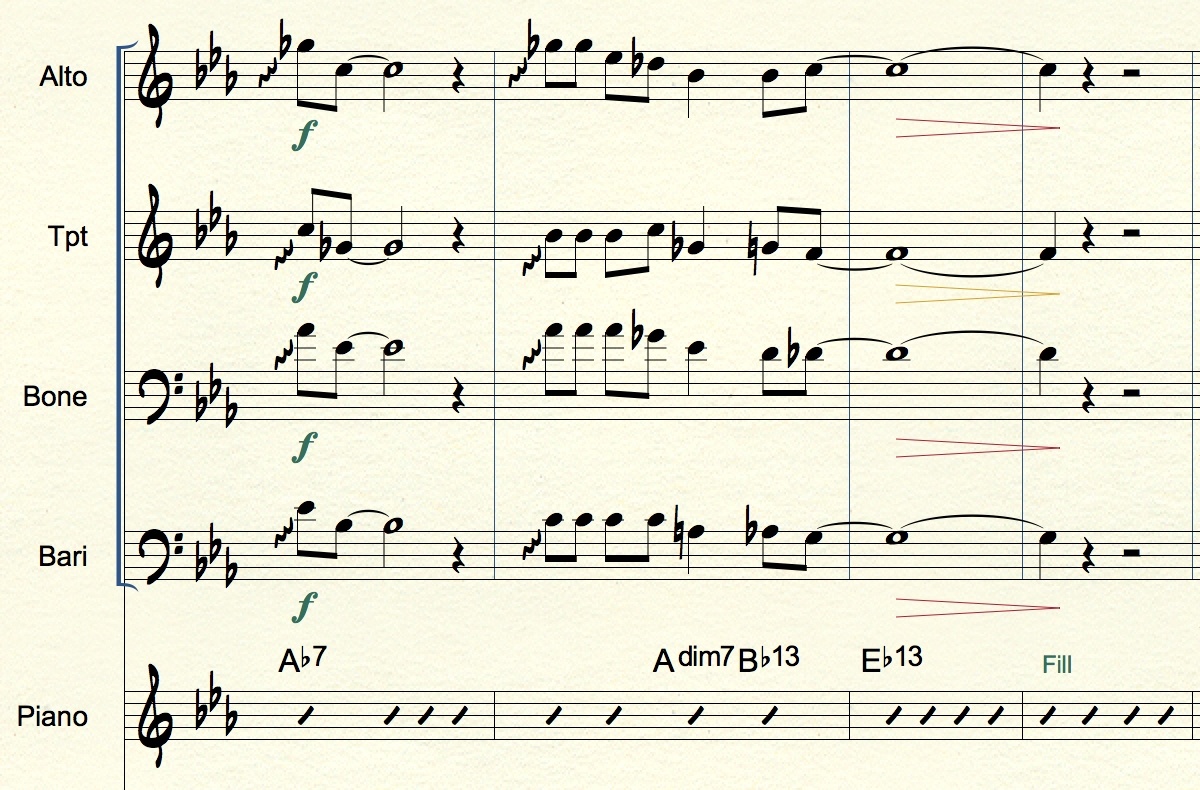

Not only does he vary up the featured interval, he also presents chord voicings for the first time in the arrangement, 13 bars in (and they say that Bill Holman was a pioneer of contrapuntal writing!). These voicings are super efficient–covering a bar of Bb7, they start on a strong beat with a Bb major triad and move stepwise down to an F-7 voicing (the II-7 to the V7 that is the Bb7). Following that, over two hits Ellington covers every available chord tone and tension of Bb13–Bb, C, D, F, G, Ab. Eb is not present because it’s an avoid note on this mixolydian chord scale. This is extremely functional and rule-abiding but primarily musical in function.

The Solo Backgrounds

The head is only presented once, with no repeat. This might be because Ellington arranged himself into a corner and wrote background parts that were a bit more interesting than Hodges’ original melody, and Ellington felt like once with that theme was enough. When Ellington repeats himself, he likes to add variety, so here if he were to repeat the head, there’s almost nowhere to go. So on to the solos we go!

Johnny Hodges gets a solo on nearly every chart in his band (out of dozens recorded over the years), and usually takes the first solo. Sometimes he even takes both the first and the last, double dipping and leaving his band mates nothing but scraps. Hodges famously had a contract with Duke Ellington’s big band that guaranteed him a minimum number of solos and features per night. The guy really liked to play!

But here, Ellington puts Hodges on the bench and lets Cootie Williams take the first solo. At first this seems to break the pattern of the Hodges book, but in retrospect it becomes clear that Ellington wants Hodges to take a burning solo that leads into that aggressive written alto part that leads over a shout section. Having any other instrument solo into that shout section would be too abrupt a shift in tone, so it was critical that for the shout chorus to succeed, Ellington would have to give the final solo to Hodges to tie it all together. This is an example of writing with foresight (something that can be effectively practiced by writing out your form and some textual ideas before you write your arrangement).

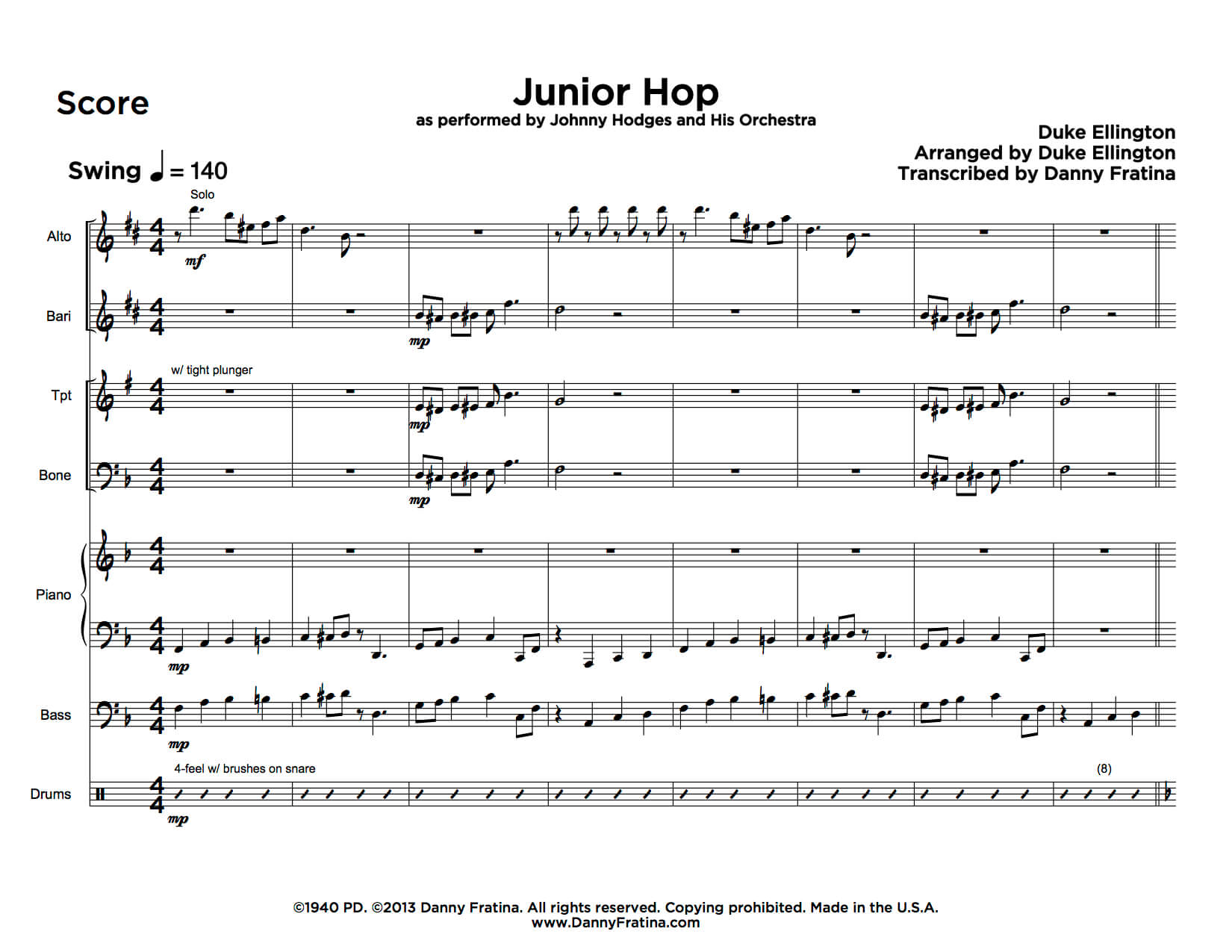

Now, the trumpet solo backgrounds sticks with the original countermelody, adding Hodges into the mix and dropping the original Cootie background line entirely, never to be seen again. Cootie Williams gets two choruses to blow over, with no change in the backgrounds. It’s an active harmony, but Williams strips it down to the essentials and treats it like a 3-chord blues he knows it fundamentally is, instead of trying to make the changes.

Johnny Hodges comes up next, and Ellington finally provides a sense of relief by giving us the changes that Cootie spent two choruses insisting on. Despite the simplified changes, Hodges is the more harmonically creative soloist and seems to almost flaunt the simplicity under him.

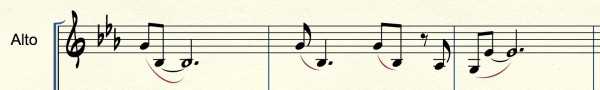

Here now is an important lesson for young arrangers. Where do you find the material for solo backgrounds? Sometimes it’s as easy as: recycle your main idea. Here, Ellington goes back to the interval well and produces a simple but thematically consistent set of background lines:

Notice the trumpet part, where I have indicated two sets of intervals: the first is the 3rd between the first two notes, and the second is the 6ths between the outer two notes. The two main intervals of the head. This is efficiency that Beethoven would be proud of. Duke Ellington uses every part of the animal arrangement. (The trombone and bari parts simply harmonize within the triad.)

And, like every chorus before, when he gets to the third phrase he opts for contrast, now using whole note voicings:

The first is a spread voicing, with the two guide tones (D and Ab) in the lower two voicings and a tension 9 (C) in the trumpet. The two guide tones then resolve baroque style, and for the extra juice, the trumpet stays on the 6 (C), creating a C- triad.

This happens twice before the rhythm section and Hodges make their way up to:

The Shout Chorus

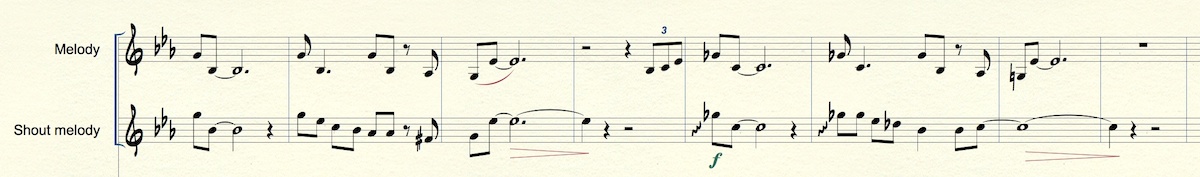

First off, take a look at that Hodges lead melody in the shout chorus. It took me years until I recognized that it was just a variation on the original alto melody. I think this is because the original melody is so buried under the multiple counterpoint lines (which I always found more interesting), and in the shout chorus it’s an octave higher and filled in with the horn harmony (which also captured my attention more than the lead part), so I never put two and two together!

But look at how similar it is. Again, Ellington writes with such efficiency. Also note how the new material in bar 2 and 6 make strong melodic statements–remember this because we’re about to come back to it.

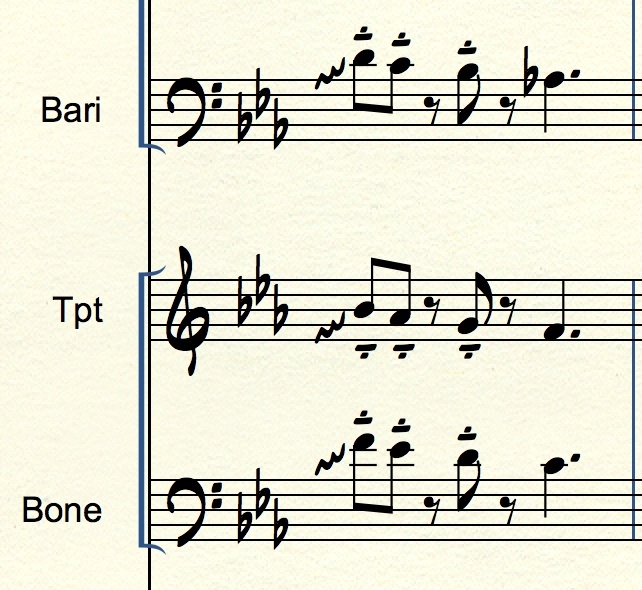

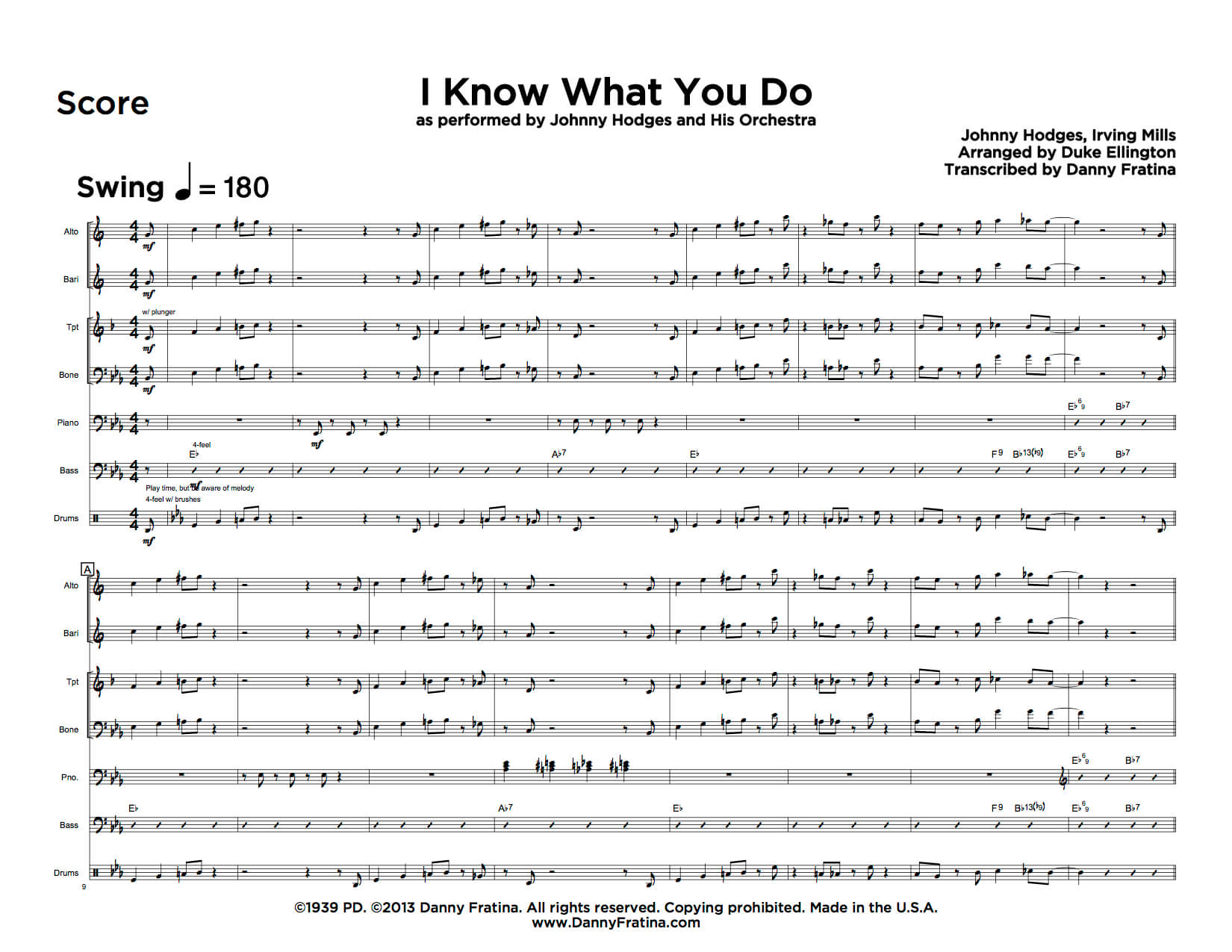

Another interesting development here is that for the first time in the entire arrangement we get 4-part harmony. Ellington waits until the 65th bar, over two minutes into the performance, to utilize all four horn players and put them in harmony together in concerted rhythm. That takes restraint, patience, and confidence. And ultimately this helps create a bigger impact and gives Ellington room to get weird. Let’s take a look at this incredible harmony, phrase by phrase:

Shout chorus, phrase #1

I’ve resorted the instruments to make vertical chords easier to read.

The first bar is a simple closed four on the Eb6. On the downbeat though, Ellington opted to make the first G easier to hear and better supported (it is quite high for alto to come right in on) so he doubled it 8vb and dropped the Bb from the voicing. The 5th, in this case the Bb, is often one of the least “important” notes in a voicing, as it’s inclusion does not generally define the sound or function of a chord. So for that strong downbeat, we get a doubled G built with a C Eb G triad on that Eb chord, resolving quickly to a closed four Eb6 voicing. Efficient.

In bar two, he again reinforces the high G for the downbeat, then lets the upbeat Eb be reinforced by the bari 8vb. Skip ahead to beat 3, an F-7 (the related II-7) voicing with the trumpet moving from the 9 to 1. With that as his target, he then works backwards, putting a Bb7(#5) voicing on the upbeat of beat 2. The downbeat of beat 2 is harder to justify at first glance, but it makes sense in context. It’s an Eb6 voicing of some sort, with C Bb G and C, but it’s not a triad. It does, however, again reinforce the alto note, and the choices of the Bb and G in the trumpet and bone respectively gives their individual lines independence and unique musicality. Keep that in mind because “unique musicality” and “line independence” are going to come back soon. The final note of bar 2 is an F#dim7 voicing. All functional so far.

Bar three gives us a perfect Bb13(b9) voicing of G D Cb Ab, or 13 3 b9 b7. The upbeat is a simple Eb7 voicing with no bells or whistles. Ellington opts for half step motion in the lower three horns (this idea will come back in a couple more bars so remember it) while the alto skips up the higher Eb. Line independence taking precedent over mechanical voicings. That gap of a major 9th between the alto and the trumpet is forgiven because of how strong the voices are on their own.

On to:

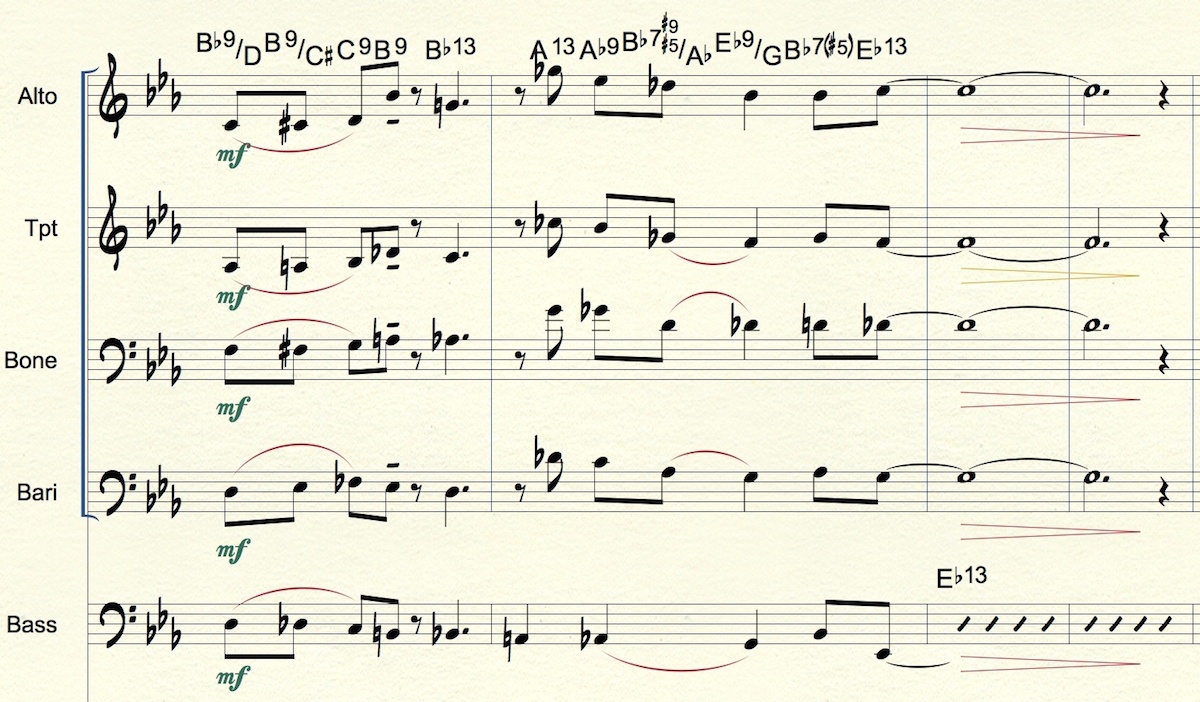

Shout chorus, phrase #2:

Here, Ellington has decided that the alto’s independence and designation as lead player has been properly established in the ear of the listener, so he ditches the reinforcing concept and settles into 4-part harmony with no doubles. In bar 1, he gives us a 4-part Ab9 voicing. I’m not 100% convinced that Lawrence Brown didn’t accidentally play Ab instead of a possible Bb (the 9th), but either way, the voicings are strong in drop 2 form, a great mechanical voicing option for this type of instrumentation.

Bar 2 is where things start to get fuzzy. Beat 1, 1.5, and 2, are Ab9 voicings, though slightly incomplete. I believe that Ellington is choosing these for the melodic possibilities they present the individual instruments. The chord sound is well defined by now, we had a full bar of strong Ab7/Ab9 voicings, so thinning it out in favor of melodic independence it perfectly reasonable and in line with Ellington’s M.O.

This applies even more strongly to beat 2.5. Db C Gb C. Half step, tritone, tritone. A voicing that would fail any arranging class at a university, but that sounds amazing here. Why? I think it’s because the alto melody came first, and Ellington had no choice but to double down and put Ab7 guide tones to help ground the voicing. The trumpet had to go to C because melodically it sounded awesome going next to the Gb. Thus trombone had to have a Gb and bari needed to stay on C. Line independence balanced with chord clarity. Beat 3 has an Adim7 voicing in the lower three voices, including the two chromatic notes that help define the chord, the A natural and Gb. But the alto have a Bb, aka avoid note b9. Again, the lower three voices ground the chord, allowing almost anything to be played above it. But the melodies are strong, and Ellington can get away with breaking the rules.

These note choices also help connect the three lower horns to beat 4, a perfect Bb13 chord of Bb G D Ab, which then resolves to a perfect spread voicing on Eb13, derived via a drop 2, or melodic strength.

In just a few bars, Ellington weaves in and out of simplicity, sonority, harmonic uncertainty, and back again. And it’s all done with a combination of voicing mastery and strong melodic writing. This might be categorized as “line writing” as it was later known, a concept taught by Herb Pomeroy at Berklee. Check out this article and the quoted sections and see if some of this rings a bell, including the paragraph at the end directly about Ellington.

Shout chorus, phrase #3

Oh but we aren’t done yet. Remember how by the 9th bar of a classical blues you need a new response statement? Ellington holds to that formula even in this 6th chorus of blues and gives us something new:

I’ve added chord symbols at the top to help make it easier to follow, and I’ve added phrase markings to highlight chromaticism that is otherwise trickier to explain.

We first need to consider the entire first bar to take place over the V7 chord, or, Bb7. With the first and last rhythms being a Bb7 chord, Ellington simply shifts up then back down, chromatically, to go to and from the target chord. Closed 4 voicings for the first three notes are made more interesting by contrary motion in the bass, which also helps create ambiguous voicings on beats 1 and 1.5. There’s no piano here to help fill things in, so this crawling harmony has nothing to help prop it up except its fundamental functionality and melodic strength. By beat 2.5, the lower three horns move to spread voicings while the alto maintains melodic independence. Which leads to absurd voicings like a B9 with a Bb in the lead.

Bar 2 continues this chromatic approach. It’s all functional, with chromatic bass motion to help unground it. The Eb9|G doesn’t sound like a too-early home chord because of that inversion and because of the chromatic way it’s reached.

This passage is minimalist, efficient and colorful. Each line maintains independence, with even the bass getting in on the fun. I mean honestly, it’s nothing short of brilliant, and an absolute standout of the swing era. Ellington gives a master class in saying the most with the least.

Going back to Herb Pomeroy, he once said in an interview, referring to Duke’s band:

Even within the ensemble, they weren’t improvising as far as the pitches. But their feeling, their sound. I mean, with Ellington, within the sax section, it is not five saxophones trying to blend with the lead player. It’s five individuals totally being themselves as far as expression, to the point that by certain standards of accurate instrument section playing, it was bad.

Ellington sets his players up for success by writing this concept into the chart itself. Johnny Hodges hired brilliant artists to play in his band, influential pillars of their instruments. But it is Ellington’s quantum writing that makes this soloists play both as individuals and as a section.

Skunk Hollow Blues is a true hidden gem of the swing era, a joy to play, and a blast to dance to. You can purchase it here.

Hi Bowie,

It’s not so much that Ellington didn’t like to reuse melodies, but that he liked to add variations. As for the alto in the shout chorus, the simplest explanation for this choice is that it was Johnny Hodges’ band, not Duke’s! So with Hodges as the star, Ellington wrote more solos for him and more lead parts. Hodges also wrote this tune (despite Duke arranging it), another reason why he would be on the top of the main sections.

The best way to learn this craft though is probably through transcription. Listening as much as possible will put the music and all the subtle details into your soul, but transcription is the process that reveals those subtleties and brings them out into the open. Ellington himself was primarily self-taught and learned by listening and by playing. His personal style developed by getting a band together early and just writing, seeing what worked and what didn’t. The world works differently in 2020 and it’s not so easy to get a band together together and spend your time writing and playing, but at the least, transcription is as close as you can get to taking lessons from Ellington himself (or whoever else you might choose to “study” from).

I’m currently studying film composition and the need to know which instrument can carry the melody best in a certain setting is not only present here with Duke Ellington but in film as well. I wanted to ask how exactly other than attending live concerts each nights would a musician be able to hone this ability (specifically if there are charts or books to be studied that Ellington himself might have learned this idea from)?

In Film Composition we commonly have to decide which instrument is the most important to take up the melody so that the film itself benefits from the choice. It’s obvious that Ellington was wary of this need since he had Hodges solo into the Shouting melody, which is a much more complex melody than the first. My own question is that you mentioned that Ellington didn’t like to reuse melodies, but I noticed the Alto melody from the beginning becomes the main melody in the shouting chorus, so does that mean that even Ellington was willing to break his own rules to carry the right melody across a song?

Pianist here. Have been studying Bill Evans 20 years. Always discovering tempo, notes, phrases hadn’t seen before. Must be part of our music progression.