One of the hardest jobs for a lead trumpet player is reading high notes, a skill that involves a strong ear, confidence, and experience. There is a clear divide that separates trumpet players who can play high notes and trumpet players who can play lead and effectively perform in the upper register. If you can simply play high notes, you can make sounds in the upper register, sometimes loud and clear, sometimes weak and flimsy, but all music needs context, and being able to pop out notes in the practice room does not necessarily translate to the real world of an actual musical performance as it happens in real time. Reading high notes is a quintessential lead trumpet tool.

If you play lead, you make music in the upper register and play consistently and confidently. A lead player treats the upper register as an extension of the normal trumpet range, and it requires extra skill and endurance to execute these arduous passages. And because of principles of acoustics forcing our ears to recognize the highest identifiable notes as “melody,” the lead trumpet role is melodically the most important and requires complete clarity. You have to set an example for the rest of an ensemble as the members play in concert with each other. It’s this factor–the music beyond the physical high notes–that sets a lead player apart, and it’s this skill hurdle that a serious player must overcome if they are to make beautiful music on this physically demanding instrument.

High notes are not driven by “chops,” as is usually assumed, but by a strong ear

Your ability to hear high notes plays the biggest role in playing high notes. Most “how-to’s” on playing high notes involve endurance exercises and loud, difficult patterns that tend to principally be for finger speed. These are focusing on the wrong goal, are lacking context, and do not contribute to the improvement of one’s fundamental musical skills, which, again, are the key to playing effectively in the upper register.

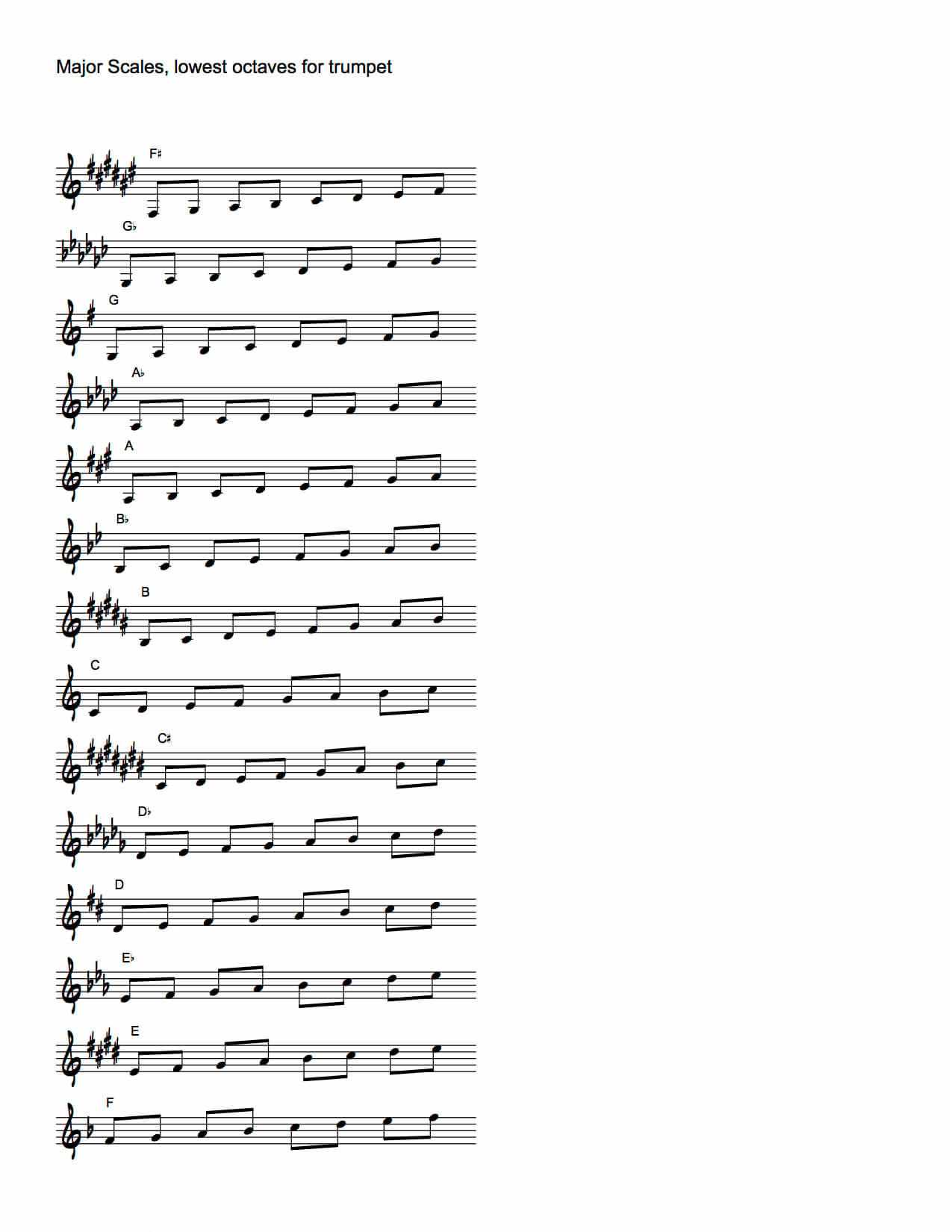

Major scales

If you are just starting out and you are interested in improving your range in a practical way, the first thing you can do is to master your major scales. Major scales have consistent recognizable patterns and sonorities and it’s easy to recognize when you are right or wrong. You can use logic to figure out new notes and assemble scales you wouldn’t know otherwise. A primary goal of scales is finger strength/muscle memory, but we are hijacking that goal: by using a strong musical pattern that has universal applicability, if we get past the finger difficulties, we can use these scales for our current goal of high range extension. This hits many short and long term goals at once.

If you are serious about extending your range, save yourself a few years of struggle and start memorizing your major scales now, and start focusing more on the “hard” scales. Our C scale is probably easy by now, but what about our B scale? Gb? Db? E? Those are now your priorities.

How to practice

Get out the metronome and a notepad. Start tracking your time spent on scales and your tempos for each one. Never play for more than 15 minutes on your scales. 15 minutes a day for 3-4 days a week, with proper tracking, will provide results within a few weeks or months. Be sure to vary your articulations, using a mixture of slurs, articulations, etc. That factor is worth tracking too. Ab scale at 134 bpm, staccato, Gb scale at 158 bpm, slurred, and so on. Go in both directions, and alternate starting from the bottom or the top. Track all of this.

Get your lowest octave as perfect as you can. Speed is not the goal, proficiency is. By this I mean do not aim for faster speeds if you have to sacrifice precision. Work your way up the metronome, click by click, only after you have been accurate at each point along the way. Go from 60 bpm to 63 bpm, or 150 to 154. Gradual increases are key. Push yourself with patience and make sure to be energetic with your fingers.

Pushing forward

As you get comfortable with all 12 major scales, from the low F# up to the first octave of our F scale, it’s now time to build that second octave.

Stay within your 15 minute window and continue to document your work. Start with a “low” scale, like F# or G. Vary up your approach: start with just the upper octave, go from the bottom up and back down, go from the top down and back up, add the lower octave and play the full two octaves from the top down, etc.

Over time, you’ll start to add the 2nd octave of other scales. Don’t jump too big of a gap – if G and C are your easiest scales, don’t learn your two-octave G scale and then your two-octave C scale–add the Ab, A, Bb and B scales first. Work your way up. Be methodical and studious. Be patient, but be flexible enough to not make each run so similar that you get bored. Boredom is a natural side effect of practicing, so be willing to balance an organic method with a disciplined method and adjust according to your personality style.

Remember, your goal is not speed. Your goal is precision and getting these notes into your ear. The intervals of major scales are all close together, so the hardest part about extending them into your upper register is how easy it is to hit the wrong partial. The slower, deliberate method described here trains your ear to know when you hit that wrong partial and helps you make quick adjustments. Those adjustments and those correct notes start to build connections in your brain that link the symbolism of a note on the page with a sound in your head, in lockstep with your fingers being in a instantaneous position, and with your embouchure in a pinpoint precise setup.

Two final notes on this. One is regarding dynamics. It will be tempting to blast these scales out as you get higher. The harder option is to maintain the same dynamic level as the lower scales. “Room dynamic,” if you will, of that mp-mf range. After that, for building physical endurance, try playing the scales with good tone at the quietest dynamic you can manage. This requires a surprisingly large amount of air, carefully regulated, and strong chops to keep good tone, but it builds up further from that and leads to great results. There is a lot to gain from avoiding loud dynamics on this exercise.

Second, if your top range of notes is not coming out well, stay at it. If you want to play a C above the staff, you don’t practice up to the C, you practice up to a Db, D, or Eb. Those top notes might be weak or inconsistent, but it gives you a new cap that makes your C stronger. If you want that high Eb to speak more, don’t stop there, aim for high E and F. For a while, your highest reachable note will not be strong, but it helps ensure the notes just below it ARE strong, and if those are your actual practical top notes you need, then the struggle for the notes above it will lead to the success you want.

This sets the foundation for building range in a practical, usable way, that covers basic melodic material with the side bonus of working up your finger proficiency and embouchure endurance as you practice fundamentals. In Part II, I’ll share some more advanced creative exercises you can use to take this to the next level.

Leave A Comment